Port Created March 6, 1915

Creation of the Port of Kennewick was initiated by the Kennewick Commercial Club, which wanted to capitalize on the Celilo Falls navigation canal (Celilo Canal) opening in May of 1915. The Port creation had strong community support, with 282 out of 379 voters (75 percent) supporting the Port’s creation.

The opening of the canal allowed river traffic from Portland through the Cascade Canal and Locks and from the Celilo Canal to the upper Columbia and Snake rivers. A grand banquet was held in Kennewick for visiting dignitaries to celebrate the canal opening and the new opportunities it represented for the region.

First two boats to pass through the Dalles-Celilo canal The Dalles, Oregon

“It is not only opportune, but absolutely imperative that Kennewick should be awake and doing her share of this toiling, hoping, progressing. The first step to take is the creation of a port district.”

Kennewick Courier-Reporter Editorial, March 1915

The Port of Kennewick immediately began to operate docks, approach and landing facilities, leasing these facilities from the Kennewick Improvement Corporation (a private entity that had organized in 1909 to develop the facilities) for $1 per year. By the summer of 1915, shipments of cargo and passengers were leaving from and arriving at Kennewick’s docks.

In 1916, the Port held a public hearing and adopted its first Comprehensive Scheme document, which needed voter approval before any funding could be expended. Included in the Comprehensive Scheme were modest proposed improvements to the Ivy Street Terminal, a suggested concept to close off the upstream end of the channel between the shoreline and Clover Island, and dredging to create a boat basin. The comprehensive scheme was approved by a small majority (118 to 97), with some controversy regarding whether the public or private sector should be paying for proposed improvements.

The Port’s budget was $2,000 in 1916 and $1,800 in 1917. During this time, the Port constructed the Ivy Street Terminal for handling cargo and passengers, and also authorized the building of a new warehouse next to the waterfront to handle record-setting cargo volumes. In 1917, the Port purchased the previously leased land and assets from the Kennewick Improvement Corporation for $1,200. The following year, steamboat activities came to a halt due to rail competition and barges, which began replacing the less efficient steamboats.

The drop in steamboat traffic and rises in rail and motor vehicle traffic spurred the Port to refocus its activities. For the next several years, the Port concentrated on building rail- and water-transfer facilities and warehouses.

Celebration of Celilo Falls Canal opening in Kennewick

Docking & Loading Facilities for Boats, Barges

In the early 1900s, the Port of Kennewick provided docking and terminal facilities for steamboats, as a direct result of the opening of Celilo Falls navigation canal. The Inland Empire was one of the boats that traveled to Kennewick, where it served as a local ferry for several years, moving goods and people in and around the area from the Port’s docking and terminal facilities. A significant flood occurred in 1926 that severely damaged the Port’s dock and loading facilities, causing a period of Port inactivity until the 1940s.

In the early 1940s, World War II stimulated docking and loading activities in the Port. In 1941, the Port acquired a portion of Clover Island and leased property to Columbia Marine Shipyards for a barge-building site on the island. This barge-building site complemented the Port constructed bulk grain conveyor and elevator, and a dock extending more than 390 out into the Columbia River from the mainland just downstream of Clover Island.

- The Winquat, once considered the most powerful tugboat in the world, was built on Clover Island in 1944

- Port dock facility in 1922, just downstream of Clover Island

- Port of Kennewick Facilities Circa 1920

- Ivy Street Terminal (Port of Kennewick 1941)

Two 175-foot barges were built and launched at Kennewick in the 1940s, and one was christened the Port of Kennewick. In 1944, the Winquatt, once known as the most powerful tugboat in the world, was also built at Clover Island.

Another large flood occurred in 1948 that caused significant damage to Port barge and boat loading facilities, and this ended the Port’s involvement in these type of facilities in the vicinity of Clover Island.

After the Port District boundary expanded in 1954, the Port constructed a dock and waterway at the Hedges Industrial Area in Finley to serve the chemical manufacturing businesses beginning to locate in that area. In 1967, the Port sold the Hedges land and presumably the associated water facilities to the Collier Carbon Chemical or other industrial businesses in the area, ending the Ports involvement in dock and barge loading facilities.

Download the History of the Port

2016 – 2025 Highlights Flipbook

View or Download PDF Files

Top: Port Commissioners, A.I. Smith, George R. Turner, and Harry A. Linn attend the launch ceremony for a barge named Port of Kennewick, which was built on Clover Island.

Left: Schematic from 1955 Comprehensive Scheme for Development Plan illustrating Camp Two Rivers

Present-day Two Rivers Park was once identified as a Port industrial site for barge-loading facilities.

Historical & Current Port District Boundaries

The Port of Kennewick District boundary originally extended south from the Columbia River at the middle of the present-day Columbia Park Golf Course, to the intersection of US 395/10th Avenue, and then due east along 10th Avenue to the Columbia River. In 1954, after seven years of construction, the McNary Dam was finished, which provided flood control along the Columbia River and improved navigation to the Tri-Cities area.

The dam created new opportunities for the Port of Kennewick, with improved navigation and more river-accessible land in the City of Kennewick and Benton County. These opportunities led to an expansion of the Port District, additional Clover Island development, and heavy industrial development in the Finley and Hover areas of east Benton County. Property acquired by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and associated with McNary Dam construction was designated for industry, recreation, and habitat, and industrial land was made available to public agencies. This additional industrial land was made available to the Port, which led to a proposal to expand the Port District.

In November 1954, 75 percent of voters approved the expansion of the Kennewick Port District to include an area constituting 485 square miles and comprising the eastern half of Benton County.

Port of Kennewick current boundaries

Port Supports the Navy During World War II & Later Invests in Rail in Downtown Kennewick

In 1942, representatives of the United States Navy called on the Port of Kennewick Commission to support the war effort by relinquishing to the Navy supplies of railroad steel and ties the Port had on hand for completion of a railroad spur track to Port facilities. The Port Commission felt duty-bound and obliged to the Navy’s request.

Rail was a primary means of moving products to and from the Port of Kennewick and other industrial properties in Kennewick during the 1940s. In 1941, Kennewick was served by three transcontinental railroads and originated thousands of railcars filled with frozen foods, canned goods, dressed poultry, asparagus, grape juice, cherries, and other commodities.

The Port had plans to develop additional rail spurs in the industrial areas of downtown Kennewick, but in 1942, the Port, in response to a request from the Navy, supported the war effort by donating steel and railroad ties.

Rail development plans were placed on hold until after the war, and the Port made substantial rail investments in downtown Kennewick during the 1950s.

Vista Field WWII History

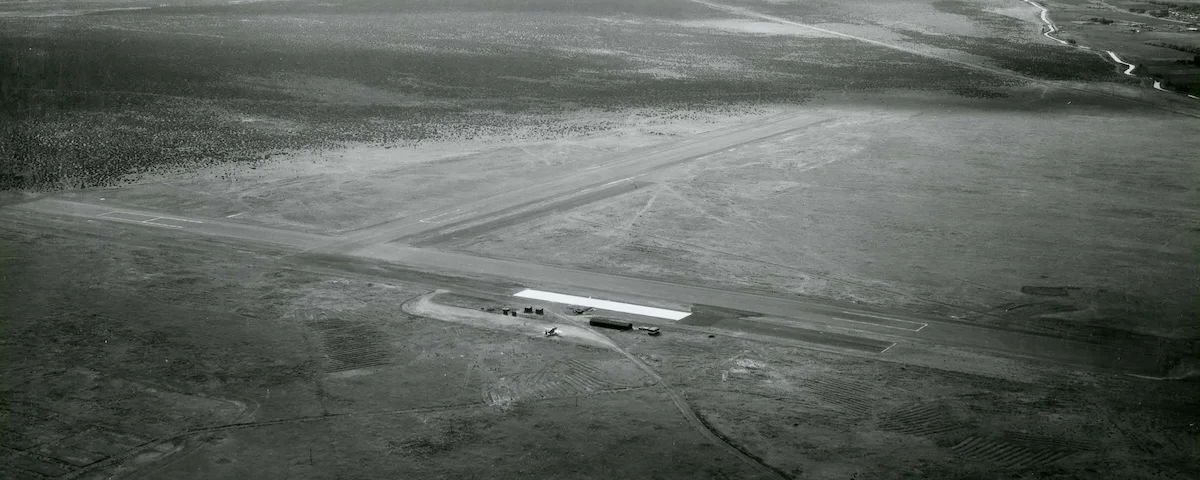

From early 1942 until April 1, 1947, the U.S. Navy leased Vista Field (a municipal airfield the Port later acquired) to train naval aviators for the war effort.

The Navy called the site Naval Auxiliary Air Facility (NAAF) Vista, and it played a crucial role in preparing aviation cadets based at Naval Air Station Pasco for combat in the Pacific Theater. Vista Field was among the first and largest auxiliary fields in operation in Washington state.

“Vista is essential for the training of Fleet Air Units that may be based at Naval Station, Pasco, Washington. The field is equipped with CV [carrier vessel] catapult and arrested landing equipment and is the only outlying field available for field carrier landing practice and other training.”

Commander of Fleet Air, Seattle

In May 1944, a crew from the 12th Battalion of the Seabees installed a 460-foot-long runway made of interlocking pierced steel planking, known as M-1 matting, to provide a more realistic experience for World War II aviators. This metal “ship deck” (pictured above) simulated the conditions of the aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-16).

The naval student pilots sharpened their takeoff and landing skills using the runway’s rough surface and limited space to perfect the precision maneuvers they would need to execute at sea.

Training each aviation cadet required 84 hours of flying time, including 38 hours with an instructor.

Aviation cadets stationed in the area logged more than 260,000 flight hours during primary training, with 1,878 graduates.

1950s & 1960s Industrial Development (Chemical Row)

The Port acquired several industrial properties during the 1950s and 1960s in the Finley area. In 1956, after McNary Dam was constructed, the Port leased 314 acres of Columbia River waterfront land for development from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Between 1953 and 1968, seven major firms established industrial operations in Finley, and the area became known as Chemical Row. These operations supported the U.S. Department of Energy Hanford Site Operations and produced fertilizer inputs to support the growing agricultural industry. A good example of this development occurred in 1957 when the Phillips Pacific Chemical Company built a $15-million plant to produce anhydrous ammonia. The plant employed nearly 100 people and was considered the area’s largest private industrial development at the time.

The Chemical Row area was known for its central location, ample transportation, low-cost power, and plentiful water. Total private investment in the Finley area from 1952 to 1964 exceeded $23 million and resulted in approximately 250 new jobs. Most of these plants are still in operation today. Sandvik Special Metals also located in the Finley area and is currently a thriving business.

The Collier Carbon and Chemical Corporation bought a 40-acre site from the Port of Kennewick for $140,000 at the present-day Hedges Industrial Area (now owned by Agrium), and the plant was finished in 1967.

1953 to 1968

Chemical Row Finley Area

1953 Allied Chemical (now abandoned)

1957 Kerley Chemical

1957 Phillips Pacific Chemical (now Agrium)

1958 Gas Ice (now Air Liquide)

1960 Cal-Spray Chemical (now Agrium)

1967 Collier Carbon and Chemical Corporation (now Agrium)

1968 Sandvik Special Metals

City of Kennewick Water-Supply Facilities on Clover Island

The City of Kennewick had water supply facilities on Clover Island from the 1950s through 1980. The first system was a filter bed in the “notch” area of the island, with pump stations just upstream, which were installed in 1952. This system only lasted a few years before failing. Then, in the late 1950s, the City installed three Ranney Well collectors housed in round, concrete structures. These were located on the northern side (river side) of the island. In 2002, two of the three Ranney well pumps were removed and the collectors were leveled and capped with concrete slabs. Safety railings were added, turning the slabs into viewing platforms.

City of Kennewick Ranney Well collector on Clover Island originally and then converted to a viewing platform

1990s & 2000s

During these decades, the Port sold numerous underutilized properties in Plymouth and Finley.

Additionally, the Port purchased land in Kennewick, Richland and West Richland to hold for potential future economic development opportunities, including 160 acres in the area now known as Southridge and the former Tri-City Raceway.

Port investments and land sales between 2007 and 2024 resulted in the creation of nearly 1,300 jobs, over 996,000 square feet of new buildings and private-sector investments of more than $192 million.

What began as a modest port focused on just a few services has grown into a multifaceted organization providing a variety of economic development services in the Port District for the region.

A few notable Port projects during this timeframe are the Business Development Buildings program, Vista Field, investment in the Southridge area development and Spaulding Business Park.

Business Development Buildings

In addition to Port of Kennewick’s 110th anniversary, 2025 also marks the 40th anniversary of the Development Building Program, which the Port launched in 1985, to provide startup or expanding businesses with scalable spaces to meet their needs.

The program was based on findings from a business trip to New York City by Port Commissioner Gene Spaulding. Upon his return, he successfully pitched the idea to his fellow commissioners, leading the Port to construct or acquire development buildings in its Oak Street Industrial Park and later at Vista Field, totaling seven development buildings.

Notable businesses have participated in this program and created hundreds of jobs. TiLite is one of the most prominent Port success stories. During its time at the Oak Street Industrial Park, TiLite grew from a small startup company into a thriving, 140-employee enterprise before moving into a company-owned building.

At Vista Field, development buildings have housed many high-tech businesses, including KeyMaster Technologies. That company was a local handheld X-ray device business that used Hanford Site technology, which was spun off for a private sector application. KeyMaster Technologies, which had become one of the world’s leading analytical instrumentation companies, was acquired by the German enterprise, Bruker, in 2006.

The Port continues to provide development space today.

Oak Street Development Building A in 2009

Vista Field

The Port acquired Vista Field from City of Kennewick in 1991. This former municipal airfield opened in the 1940s to serve local farmers and flying enthusiasts.

The Navy leased Vista Field to train pilots during World War II (read about Vista Field’s wartime history earlier on this web page).

In spring 1947, the Navy ended its lease with the City of Kennewick, and thereafter, Vista Field served as a general aviation airport using the code VSK. The Port operated Vista Field from 1991 until December 31, 1991, when the decision was made to close the airfield due to declining activity.

The Port hosted public planning sessions to reimagine Vista Field, and today is transforming the 103-acre site into a vibrant regional town center.

Vista Field Entry Building in 1991

Southridge Area Development

Port of Kennewick purchased the Dickerson “Southridge” property from the Washington State Department of Natural Resources in 1994. The Port named the property after Dave Dickerson, who served as a Port of Kennewick Commissioner from 1977 until his passing in 1992.

The original site included 160 acres of Port property, primarily on the west side of US 395. In 2002, the Port co-funded the Southridge Area Master Plan for a 2,500-acre area with the City of Kennewick, the Benton Public Utility District, Kennewick General Hospital and Kennewick School District. The City completed the Southridge Master Plan in 2004, which identified nearly all the Port’s land for future commercial development.

Realizing the land would not remain zoned for industrial use as originally intended, the Port traded a portion of the site to Trios Health for a new hospital site. The Port also collaborated with the City of Kennewick to establish a local revitalization financing arrangement (commonly known as tax-increment financing) to support Southridge development. This partnership allowed local tax revenues generated in the revitalization area to fund infrastructure investments at Southridge.

In 2019, the Port sold its final parcel in Southridge, having helped spur the steady pace of development, including Southridge High School, restaurants, retail shops, single- and multi-family housing, the City of Kennewick sports complex, the Carousel of Dreams and the new Trios Health hospital.

Development in Southridge has created several hundred jobs, and the area continues to grow.

Southridge Development

Spaulding Business Park

In 1999, the Port of Kennewick purchased approximately 30 acres in the Richland Wye area, where the Yakima River enters the Columbia River. The land would be the future home of the Spaulding Business Park, named after the late Gene Spaulding, who served as a Port Commissioner for almost 36 years and retired in 1999. After spending $610,000 preparing the land for sale, including the addition of roads, utilities and streetlights, the Port had a dedication ceremony for the new Spaulding Business Park in January 2003.

In 2016, the Port sold its final 1-acre parcel, completing the Spaulding Business Park redevelopment.

The Port’s early investment tipped that tired neighborhood into a desirable waterfront. Since 2007, private investment in the Spaulding Business Park has resulted in a new building space worth $32 million in assessed property value and more than 300 new jobs.

Today, around a dozen companies call Spaulding Business Park home.

Spaulding Business Park

Current Focus Is Urban Renewal

In the mid-2000s, the Port turned its efforts from heavy industry to economic redevelopment.

Major Port projects are revitalizing former industrial areas, forgotten neighborhoods and worn-out waterfronts to benefit the community and acknowledge Tribal homelands.

The transformations of Clover Island, Vista Field and properties like Columbia Gardens along East Columbia Drive in Kennewick are significant efforts. These projects will continue to foster business and job growth and enhance the region’s quality of life for decades to come.

Visit PortofKennewick.org/Projects to learn more about other major projects completed and underway.

In 2025, the Port celebrated its 110th anniversary and is well-positioned to provide economic development services in close coordination with public and private sector partners and to capitalize on market opportunities over the next 100 years.

- Vista Field southern gateway transformation project underway

- Clover Island following completion of the shoreline restoration projects

- Columbia Gardens Artisan Village development, showing the first private sector investment

Na Pamâw Xátwayn – We’ve Become Friends

2024 Governor’s Smart Partnerships Award for Clover Island

Over the years, Port of Kennewick and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) have cultivated a meaningful relationship built on trust, mutual respect, common interests and regular engagement.

When reflecting on the partnership in 2025, Frederick A. Hill Sr., a former CTUIR Board of Trustees member, stated: “Na Pamâw Xátwayn,” which translates to “we’ve become friends.”

Port of Kennewick’s district lies within the ceded, aboriginal and usual and accustomed lands of the Weyíiletpuu (Cayuse people), Imatalamłáma (Umatilla people) and Walúulapam (Walla Walla people) as recognized in the Treaty of 1855. This homeland is a sacred and significant place for the Tribes.

The Beginning of a Lasting Friendship

In summer 2008, the Port began discussions with the CTUIR about Clover Island improvements at its Salmon Walk event in Pendleton. It was there that Port staff first met the late Chief Carl Sampson. Communications continued with social events on Clover Island, fostering connections between then CTUIR Executive Director Don Sampson and Port of Kennewick Executive Director Tim Arntzen.

The early conversations between Tim and Don, along with their foresight and leadership, paved the way for deeper cooperation and engagement with subsequent CTUIR executive directors and staff, and led to a series of joint board meetings. Additionally, Commissioner Skip Novakovich, as the Port’s designated Tribal representative, formed a deep bond with the late CTUIR Elder Les Minthorn and other CTUIR and Tamástslikt Cultural Institute board members.

These interactions provided the foundation of a growing friendship between the CTUIR and Port.

Throughout the years, the Tribes have provided invaluable contributions to Port projects, including cultural resources oversight, letters of support and advocacy for Clover Island’s shoreline restoration.

Historic Memorandum of Understanding

A pivotal moment in the relationship occurred on February 26, 2013, when the CTUIR Board of Trustees and the Port Board of Commissioners signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). This historic memorandum solidified years of informal work together on shared interests.

Today, the MOU stands as an enduring commitment between the partners. However, what’s proven to be even more important is the authentic, personal engagement, which can serve as a guide for future generations in the hope that they will continue to strengthen and build upon this treasured friendship.

“Wiyák̉uktpa” (The Gathering Place) artwork dedication

Vista Field phase one grand opening

“The MOU was a major step and unique because our expectations are focused on friendship and understanding rather than transactions. These types of documents ensure we’re aligned and provide ‘marching orders,’ even if they go unused for long periods.”

Dave Tovey

Former CTUIR Executive Director & Nixyáawii

Community Financial Services Executive Director

Revitalizing Clover Island

The Port and CTUIR worked together to restore and revitalize Clover Island, transforming its concrete rubble-covered riverbank into a living shoreline. Those efforts not only enhanced the shoreline’s riparian ecosystem but also added a recreational path, amenities and art.

A notable collaboration is the “Wiyák̉uktpa” (The Gathering Place) art installation on Clover Island. The artwork and interpretive panels honor the CTUIR’s tradition of harvesting tule reeds and capturing fish with woven willow baskets. In 2017, the partners celebrated completion of the installation with a community unveiling ceremony, commemorating the Tribes’ ties to Ánwaš (Clover Island) and nčỉ-Wána (Columbia River).

“Wiyák̉uktpa” (The Gathering Place) art installation

Clover Island boat launch reopening

Clover Island West Causeway restoration blessing ceremony

Friend of the Port

To honor their significant contributions, the Port of Kennewick recognized the CTUIR as its 2017 Friend of the Port.

This recognition was a celebration of the CTUIR’s unwavering friendship and partnership in transforming Kennewick’s historic waterfront, as well as their investment of time, talents and ongoing involvement in Port projects. Port Commissioner Novakovich, who also serves on the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute board, expressed appreciation on behalf of the Port for the Tribes’ continued dedication.

We are grateful for the Tribes’ support of the Port and our projects. All along the way, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation have been our champions, our allies and our friends, from letters they’ve sent endorsing our grant requests, helping us restore the shoreline and engaging in regular meetings with our Commission to helping bring renewed vibrancy to the waterfront.

Skip Novakovich

Port of Kennewick Commissioner

“Wiyák̉uktpa” (The Gathering Place) artwork dedication

A Lasting Bond

The relationship has continued to flourish, not only through collaboration among CTUIR and Port leadership and staff, but also through personal connections that have developed between them. Those connections have further solidified the friendship between the Port and Tribes.

As new Port and CTUIR staff and leadership are introduced, the partners desire that this strong relationship will continue, not as a transactional one, but with meaningful interactions and cooperation on projects of mutual benefit. And that the Port-CTUIR relationship might serve as a model to other municipalities as they seek authentic engagement with Tribes.

2024 Governor’s Smart Partnerships Award for Clover Island

“The relationship and partnership between Port of Kennewick and the Confederated Tribes is a good example that all entities and Tribes can follow. Being able to communicate and work together, and having an understanding that isn’t one-sided, is something others can see and understand.”

Toby Patrick

CTUIR Board of Trustees

Port Commissioners & Executive Directors

During the last 110 years, 37 Commissioners represented the Port of Kennewick, with Gene Spaulding having the longest tenure (36 years, from 1963 to 1998). James E. Magnuson served as a Port Commissioner for 21 years—serving from 1953 to 1973. Of the remaining Commissioners, six served more than 10 years, including A. I. Smith (1931 to 1942), Paul G. Richmond (1943 to 1954), Ray F. Hamilton (1955 to 1966), Dave Dickerson (1977 to 1991), George Jones (1986 to 1997), and Gene Wagner (2002 to 2013).

The very first Commissioners

G. M. Annis, 1915 to 1916

M. H. Church, 1915 to 1924

W. R. Weisel, 1915 to 1923

Other Commissioners included:

Ingwall Smith, 1917 to 1924

G.R. Bradshaw, 1924 to 1931

Willard Campbell, 1931 to 1939

Jay Perry, 1931 to 1939

George R. Turner, 1940 to 1942

Harry A. Linn, 1940 to 1942

Ralph E. Reed, 1943 to 1944

Alfred C. Amon, 1945 to 1952

Walter M. Knowles, 1945 to 1952

Edward H. Weber, 1953 to 1956

John H. Grigg, 1957 to 1962

Wayne L. Rogers 1967 to 1973

Charles F. Markham, 1974 to 1976

Gilbert J. Ackerman, 1974 to 1978

Ray L. Elmgren, 1979 to 1985

Paul L. Vick, 1992 to 2001

Sue Frost, 1998 to 2002

Norm Engelhard, 1999 to 2001

John Olson, 2000 to 2005

Dave Hanson, 2003 to 2012

Linda Boomer, 2006 to 2008

Calvin Dudney, 2008 to 2009

Gene Wagner, 2002 to 2013

Don Barnes, 2012 to 2021

Current Board of Commissioners:

Skip Novakovich, 2009 to present

Kenneth Hohenberg, 2022 to present

Thomas Moak, 2014 to present

Port Executive Directors

John Neuman, 1955 to 1973

Robert “Hank” Thietje, 1974 to 1976

Art Colby, 1974 to 1979

Sue Watkins (Frost), 1979 to 1997

John Givens, 1997 to 2004

Tim Arntzen, 2004 to present